I chose last month’s challenge believing it would be a tricky one. However, I was truly impressed by the answers given, although none of them were correct, but the knowledge of prehistoric critters the readers of this blog possesses impresses me. I truly thought everyone would simply guess Triceratops and move on. As I said, this is not Triceratops, nor any of the ceratopsians given in the comments. Thus, this once again makes me the winner of this month’s challenge for stumping everyone.

However, the critter that owned the skull in last month’s challenge was Pentaceratops sternbergii and I will give you five guesses as to what its name means.

(Taken at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science)

Pentaceratops lived during the Cretaceous 75 to 73 million years ago. It is mostly found in New Mexico and Colorado (U.S.). It would have reached a length of ~8 meters and weighed ~5,500 kg. Pentaceratops had five horns, two large horns over the eyes, one small horn over the nose, and two small horns, which protrude sideways out of under the eyes. Pentaceratops also possessed a large frill with two large fenestrae in it. The fenestrae found on the frill were most likely away for cutting down the weight of the skull. Pentaceratops specimens include some of the largest skulls of all terrestrial animals. The frill and horns were most likely used for display, with the possibility of blood being pumped into the frill to change its color slightly. The frill and horns were also probably used in defense as well as jousting between each other.

Pentaceratops belongs to the ceratopsian clade. That clade also belongs to the ornithischian clade, meaning that Pentaceratops and the other ceratopsians are more closely related to hadrosaurids and thyreophorans than they are to saurischians. Pentaceratops is believed to be an herbivore and thought to have traveled in large herds similar to modern bovines. Another striking feature Pentaceratops possesses is its sharp beak, which was most likely used for ripping open large and tough vegetation or digging into the ground for tubers.

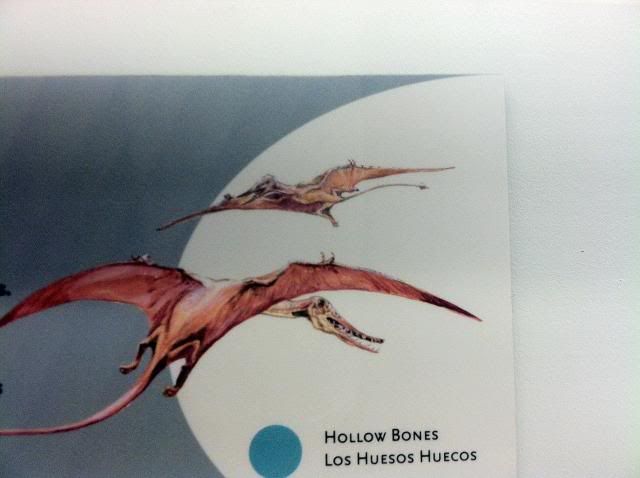

Moving on to next month’s challenge:

(Taken at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science)

Here is an easy one, since last month’s challenge ended up being so difficult. I am looking for the critter on the left, since the critter on the right was already featured. Good luck to all that participate.