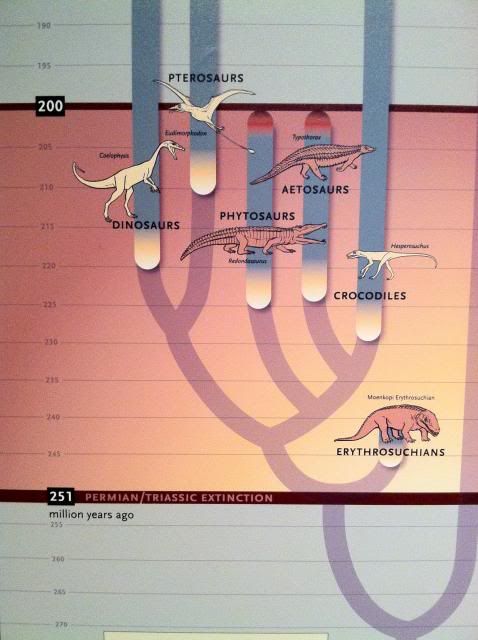

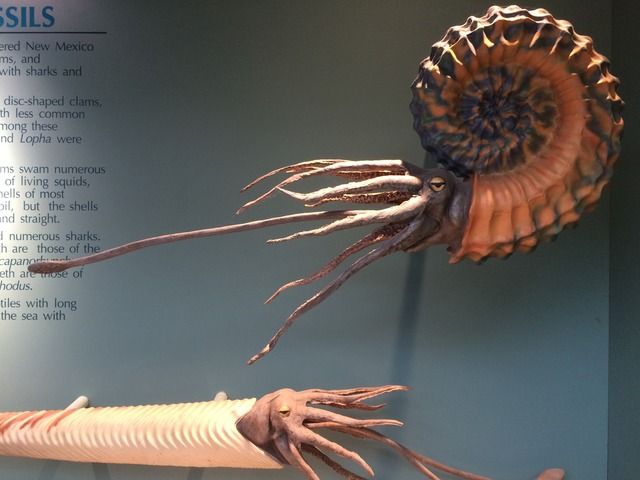

The views of creationists on “evidence” are interesting. Quite often you’ll see organizations like AiG saying that we all have “the same evidence” and what it means to the viewer depends on their worldview. This is best shown by one of their own pictures.

So, according to AiG, all that matters is your worldview. Your worldview determines how you see the evidence. The logical result of this is that evidence, in itself, says nothing. This of course contradicts the very definition of evidence, which google defines as:

the available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid

Thus, if we are to believe creationists, then there’s literally no evidence pointing to anything about our origins. None at all. All we have are bones and rocks and DNA which can be fit to match any preconceived conclusion, but these things do not, in themselves, point to any particular answer.

One must ask, then, why YECs so often push to challenge evolution. Why do they point to the rock record and proclaim “_____ is evidence of a global flood” or “_____ disproves gene duplication” or “_____ points to intelligent design.”? If creationist organizations are right, that evidence is a matter of worldview, then they cannot point to these things and say they are evidence against evolution. They are not evidence of anything, just more raw data that can be mashed into either conclusion.

I understand not all YECs subscribe to the view of places like AiG, and understand what evidence actually means. But when AiG turns around and does exactly this, claiming evidence for their position exists, then they’re contradicting themselves. Either they admit there is no evidence, and thus no genuine conclusions can be reached only assumed from the onset, or evidence does exist, in which case arguing about it being “a matter of worldview” makes no sense.

But of course they’re blind to this contradiction. I doubt that’s a surprise. I’m sure I’m not the first one to notice this contradiction either.

Until next time guys.