On the Internet, I have encountered a prominent Philosopher of Religion called Alvin Plantinga who was once described by Time Magazine as a America’s leading orthodoxist Protestant Philosopher of God. He has made many anti-naturalistic arguments and theistic arguments in the past, has engaged in Public Discourse with atheists, rather like William Lane Craig. And also, William Lane Craig seems to be a fan of Plantinga’s misguided “Reformed Epistemology”. But that’s another story altogether. In our particular case, I intend to refute the various fallacious absurdities of Alvin Plantinga’s “Evolutionary Argument Against [Metaphysical] Naturalism”. Or rather more specifically, I will be critiquing all six parts together of a six-part series of lectures on YouTube. It is a talk by Plantinga entitled “An Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism”. —see here. I may not be able to address every point as meticulously as I would like to, but I will give it a fair shot. Of course, it is doubtful that he has not simply ignored these criticisms if they have already been made in the past. Oh well… also, for expediency, here is an overview of Plantinga from Wikipedia. You will notice that like William Lane Craig, he is a Christian apologist, and has authored such books as God and Other Minds, and has even written a book entirely dedicated to the argument he presents in this 60 minute lecture. 🙂

It’s well worth mentioning that Plantinga’s argument is 18 years old or so, and it has failed to convince any naturalist in the mainstream groups of naturalists (Dennett et al). Unusual, considering that it is supposedly such a powerful argument in it’s explanatory content. Nonetheless, having watched this series of videos, it has become clear to me that Plantinga’s EAAN (Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism) as just as flawed as other theological musings such as the slippery old Cosmological Argument.

Critique of Alvin Plantinga’s “Evolutionary Argument against Naturalism” – Link:http://www.youtube.com/view_play_list?p … C36901BCEE

Before we can even begin to account the myriad flaws and fallacies of the EAAN’s reasoning and supporting arguments, it is already plain to see that the argument is unworkable. Plantinga is a strong advocate of Theistic Evolution and argues that if God created Man “In his own Image”, by means of biological evolution, then our cognitive faculties would be reliably tuned to truth. However if naturalistic (i.e., non-theistic) evolution is true our faculties would be unreliably tuned to “mere survival”. I find EAAN to be incoherent.

Plantinga argues that evolutionary naturalism is unjustifiable because our accumulated mountains of evidence for it (as well as our cognitive processes for testing/assessing this evidence) would not be trustworthy in the absence of God, the source of absolute truth. He then argues that traditional theism is more defensible on the grounds that our minds were designed by God. His argument falls apart because it intrinsically begs the question. If Plantinga conceded that this rather small point of his was indefensible, then the entire argument would fall flat on it’s face. Now, I will try to squeeze in some of my more detailed thoughts on the actual videos.

Part 1

03:15 (3 minutes and 15 seconds)

- :

- “And then when I use the word ‘naturalism’, what I really mean is … the belief that there’s no such person as God, or anything like God”

Here it would be well worth noting that Plantinga is making an implicit reference to Positive or “Strong” Atheism rather than naturalism. Positive Atheism being, as everyone knows, taking an epistemically positive stance in the form of atheism, with the positive assertion that a God or gods do not exist. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that Plantinga misunderstands both atheism as it is most commonly understood, as well as misrepresenting naturalism. Naturalism could be better defined as empirical-ism, meaning that it only accepts things on the basis of material, tangible evidence, and all evidence is still subject to be changed, or to be shown false. God, the supernatural “realm” in general, and so forth, all fall into the class of ideas and entities that are wholly unknown given naturalism. Vague, untestable, and unfalsifiable, and thus not subject to naturalistic modes of inquiry.

03:24 (3 minutes and 24 seconds)

- :

- “Naturalism is stronger than atheism. Naturalism entails atheism … but atheism doesn’t entail naturalism; you can be an atheist without rising to the heights of – or sinking to the depths of (whatever you think is appropriate) – naturalism…”

Here he goes again with his broad and unqualified statements about what “naturalism” means. One is tempted to think that this is a deliberate falsification, and not a mistake. It would have been more technically accurate and indeed, honest – if Plantinga had mentioned that “naturalism” in the context of theistic/antitheistic arguments, exists as two differing stances. One is an epistemological position, while the other is an ontological position. Namely: Metaphysical Naturalism, and Methodological Naturalism.

Methodological Naturalism:

“Methodological naturalism (‘MN’) is the commitment of scientific investigation in practice to studying only naturalistic causes and explanations. Boudry et al. observe, though, that there are really two types of MN:

Intrinsic methodological naturalism (IMN) is the a priori philosophical commitment to not even consider supernatural explanations (see the authors’ definition of “supernatural’ below). As Boudry et al. state in a forthcoming paper, under IMN ‘science is simply not equipped to deal with the supernatural and therefore has no authority on the issue.’ This is the view expressed by people like Eugenie Scott, Kenneth Miller, and Rob Pennock. It also appears to be the official position of the National Center for Science Education and the semi-official position of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the National Academy of Sciences.

Provisional (or pragmatic) methodological naturalism (PMN),’a provisory and empirically grounded commitment to naturalistic causes and explanations, which in principle is revocable by extraordinary empirical evidence.’ As the authors note:

According to this conception, MN did not drop from thin air, but is just the best methodological guideline that emerged from the history of science (Shanks 2004; Coyne 2009; Edis 2006), in particular the pattern of consistent success of naturalistic explanations. Appeals to the supernatural have consistently proven to be premature, and science has never made headway by pursuing them. The rationale for PMN thus excludes IMN: if supernatural explanations are rejected because they have failed in the past, this entails that, at least in some sense, they might have succeeded. The fact that they didn’t is of high interest and shows that science does have a bearing on the question of the supernatural.”

Source: http://whyevolutionistrue.wordpress.com … ernatural/

Metaphysical Naturalism as detailed by Wikipedia:

“Metaphysical naturalism. also called ontological naturalism and philosophical naturalism, is a philosophical worldview and belief system that holds that there is nothing but natural elements, principles, and relations of the kind studied by the natural sciences, i.e., those required to understand our physical environment by mathematical modeling. It is occasionally referred to as philosophical naturalism, or just naturalism. Methodological naturalism however, refers exclusively to the methodology of science, for which metaphysical naturalism provides only one possible ontological foundation.

Metaphysical naturalism holds that all properties related to consciousness and the mind are reducible to, or supervene upon, nature. Broadly, the corresponding theological perspective is religious naturalism or spiritual naturalism. More specifically, it rejects the supernatural concepts and explanations that are part of many religions.’

The latter, (Metaphysical Naturalism), is an ontological position, and deals with reality rather than with descriptions of reality, as does the former. Metaphysical, or Philosophical, or more appropriately Ontological Naturalism, deals with the nature of reality, and can be thought of as an extension to Methodological Naturalism. Essentially, it takes Methodological Naturalism, an essential bedrock axiom of scientific inquiry, and extrapolates it positively, to evoke belief in the non-existence of the supernatural. Or rather, that we live in a mechanistically physical reality governed by natural laws. It can be thought of in the same way that Strong Atheism is an epistemologically burdened claim, pertaining to the non-existence of God. But that’s another topic (again).

And contrary to Plantinga’s oversimplification; the naturalistic stance on the existence of God is far more of a vague one. MethodologicalNaturalism (explicitly) — does not directly deny the existence of one or more gods, like Metaphysical adaptations of naturalism do (implicitly). Methodological Naturalism, a key to scientific discovery; merely withholds judgment on the existence or non-existence of a class of “things” of which god(s) are only a part of. Namely, the group that includes the supernatural, and transcendental entities… Supernaturalism in Science should be out-ruled in principle, anyways. As such then, the Atheist vs. Theist debate in this context, and the relevance of the position of the atheist, is not so much the simple statement that there are no gods (which I believe to be an accurate statement), but rather, it is more of a pragmatic sentiment on the knowability or unkowability of the existence of God, in which case, we may as well reject the notion of gods in principle, until physical proof of it’s (or “their”, if we were to include polytheistic religions); existence.

I needn’t mention Plantinga’s later statement about the beliefs of Hegel, as I do not dispute them. The next sentence is a brief statement about the natural evolution of conscious living beings, and it’s place as part of Metaphysical Naturalism, simplistically defined, that is, as well as it’s technical relevance to the ins and outs of the rest of his argument. He also presents a brief summary of the structure of his argument(s).

04:22 (4 minutes and 22 seconds)

- … “Evolution is often thought of as kind of a pillar in the temple of naturalism, if indeed naturalism has a temple. But… I want to argue that they don’t fit together. I want to argue that … one can’t sensibly be both a naturalist, and… accept… evolution (as evolution is ordinarily thought of), and that they conflict with each other. They go against each other. The conjunction of the two – naturalism and evolution – I want to argue … shoots itself in the foot! Or as a more complex, learned sounding way of putting it: is self-referentially incoherent. “

I wondered whilst listening to this when he would get to the point, instead of tautologically repeating the same line four or five times! ![]()

Of course, Plantinga himself has in fact shot himself in the foot as well. As I said, the argument has certainly not convinced me, and it has yet to convince any serious naturalist in the thinking world, or anyone on this forum for that matter. Additionally, it’s good to see Plantinga showing his Platonic Colours again, to some degree. ![]() Plantinga has previously made apparent his Platonic Idealism, meaning that he believes that ideas represent some kind of absolute reality, and we can see examples of this cropping up all over his argument if you look hard enough, as in his Reformed Epistemology.

Plantinga has previously made apparent his Platonic Idealism, meaning that he believes that ideas represent some kind of absolute reality, and we can see examples of this cropping up all over his argument if you look hard enough, as in his Reformed Epistemology.

06:20 (6 minutes and 20 seconds)

- “So according to theism; belief in God, we human beings have been created by a wholly good, all powerful, and all knowing being, namely God, who has … created us in his own Image, made us like him… who has aims and intentions – he intends certain things – and can act in such a way to accomplish those aims. That’s part of what it is to be a person …”

I trust you will all see the conflict of definitions here, as Plantinga struggles to keep his terms straight. He starts off by using the generic and unqualified term “theism”, a label which does NOT only apply to the Abrahamic Versions of god(s), but applies moreover, to any ‘God’, or gods! And then he proceeds to “qualify” that statement with what is clearly a description of the far more specific – namely – the Judeo-Christian Monotheistic God, and even goes on to allude to the Judeo-Christian myths and mythologies about the creation of the world and universe, such as God creating man in his own image. He also assumes that this God is personal. And so, it ultimately becomes clear that although he uses the very broad term “theism”, what he is really talking about is the Christian God. It seems very strange to me that a sophisticated philosopher such as Alvin Plantinga could confuse his terms in such a bizarre way. It is not the first time he has done this, and we’re not even through with the 1st vide ( represented by*Part 1* – in huge bold green).

09:09 (9 minutes and 9 seconds)

- “In brief here’s how my argument will go …

- I’ll argue that … if naturalism and evolution were both true, if that conjunction – that pair of propositions – were both correct … then it would be improbable that our cognitive faculties – memory etc. – are in fact reliable …”

This is a truism! The overwhelming majority of naturalists accept this, and so do I! It is not merely “improbable”. It’s a fact. It is empirically verifiable, and well documented, that all of those cognitive functions are highly unreliable! How reliable were the inductive assumptions of old worldy (lol) religions about their gods and deities? How accurate were the Romans and Greeks’ perceptions on such things, with their dozens of gods?? The god of war, the god of fire, the god of… sewage. ![]() Or the Aztecs who had little objections to cutting peoples’ hearts whilst still alive, and sacrificing their parts to their gods? Not to mention the fact that the people were generally acquiescent to this rather obscure fact.

Or the Aztecs who had little objections to cutting peoples’ hearts whilst still alive, and sacrificing their parts to their gods? Not to mention the fact that the people were generally acquiescent to this rather obscure fact.

Here is one, rather random example of how our cognitive faculties can fail us: the McGurk Effect. A mysterious perceptual illusion that takes place because your senses, namely vision and hearing, conflict. This is an example of one of the flaws of our cognitions and precognitions.

It seems almost as though Plantinga is trying to assert that our everyday thinking and cognition about the world and universe is reliable and truthful. “Sadly” depending on your perspective, all of the available evidence seems to favour the opposite conclusion: that it’s unreliable, and based on limited perceptual knowledge. Heck, human beings can only ever understand their surroundings to the extent that they can ask “what am I doing now?” — by which time “now” is long, long gone. ![]()

If Plantinga is attempting to argue that human cognition is somehow perfectly reliable from his viewpoint, and there is no good reason to believe that it is, and good reasons to believe that it isn’t…. then his entire argument will collapse. Rather, the question here is whether or not certain cognitive faculties would be favoured by evolution via natural selection, and which of those faculties can be counted on to produce truthful perceptions of the world.

Next will be the final point I deal with in this video.. but there’s still 5 more….

09:36 (9 minutes and 36 seconds)

- “Well once you see that … then once you accept [both] naturalism and evolution, then you now have a defeater for that proposition. For this proposition that your cognitive faculties are reliable…a reason to give that proposition up… a reason not to believe it. And once you have a defeater for that proposition – that your cognitive faculties are reliable, then you also have a defeater for any proposition that you take to be produced by your cognitive faculties…. [ … ] so then you also have a defeater for naturalism and evolution itself. “

1. If we had to reject all of our belief simply because they might be wrong, then Plantinga’s religious beliefs stand to the same principle as the evolutionary naturalist. Assuming that Plantinga’s reasoning is correct. Unfortunately, it’s not …

2. It is not simply evolution that allows for the possibility of error.

Plantinga seems to be highlighting the fact that has been growing in my mind for quite a while. That all of our faculties, and all knowledge is but axiomatic in it’s nature, no matter how certain we are. Science operates on the possibility of error, as does much else.

Plus, Plantinga also seems to be committing to an implicit fallacy of equivocation, by assuming that all of our cognitive faculties as he puts it, are equal and equally worth mentioning. They are not. It’s pretty evident that some of these functions have been honed to a sharper degree by natural selective pressures, such as vision. In humans, we have full colour vision, and forward-facing eyes, probably one of the most advanced visual systems in the living world. Our olfactory cognition however, is seriously weak compared to other animals such as dogs and cats, as is our hearing, the senses that are usually most acutely tuned in most placental mammals other than primates.

And as for religious beliefs. . .

For an explanation of the cognitions that may lead to religion, I present for your approval, a video made by Dr. Andy. Thomson. According to Thomson, a robust and comprehensive account of religious thinking and beliefs can be arrived at in terms of our species’ biological evolution. God does not exist in our experience; we ascribe an interpretation to our intuitions, but these intuitions are byproducts of brain functioning that can be understood in evolutionary terms. Dr. Thomson: “Religious beliefs are just the extraordinary use of everyday cognitions, everyday adaptations: social cognitions, agency detection, precautionary reasoning. Religious beliefs are a byproduct of cognitive mechanisms designed [by evolution] for other purposes.”

Dr. Andy Thomson: Why We Believe in Gods

I post this as an example of how religion, may in fact have been “designed”, or created as an artifact of evolution, as an adaptation. Thomson provides robust evidence that religious belief is the result of cognitive mechanisms used in unusual ways, and even presents evidence that religious beliefs and/or misassumptions are present even in newborns. ![]() Fascinating indeed …

Fascinating indeed …

Part 2

Plantinga now proceeds to quote Thomas Aquinas on the nature of God and it’s “relationships” with human cognitions.

00:14 (0 minutes and 14 seconds)

- “Since human beings are said to be in the image of god in virtue of their having a nature that includes an intellect … they’re in the image of God because they’ve got an intellect – they can understand and know – such a nature, one with an intellect, is one most in the image of God in being able most to imitate God. So he thinks of this err … ability to “know” on our part is perhaps the most important aspect of the image of God, in human beings…”

Now I will dissect the flaws in Plantinga’s “Reformed Epistemology”, and discuss the axiomatic nature of knowledge. Plantinga almost appears to argue that our experience of the world is somehow supernatural, and citation is needed there, methinks.

01:21 (1 minute and 21 seconds)

- “Most of us would think [ … ] that at least a function of our cognitive faculties would be to provide us with true beliefs. That’s what they’re for. And we would normally think that when they’re functioning properly, when there’s no dys/mal – function, that for the most part, that’s what they do … Of course it’s true that err… let’s say err… if there are five different witnesses to an auto[mobile] accident, you might get five different stories. But there will be an underlying level of agreement … “

Is it not dangerous to simply assume that your beliefs are reliable from the outset, when you have no reliable means of demonstrating this? Also note how Plantinga simply assumes that his beliefs about the world/universe are true, and then qualifies his statement with the spurious phrase “for the most part”…. It turns out that he cannot claim to know absolute certainty, anymore than methodological naturalists. It seems that Plantinga is no longer talking about his naive notions of objective truths and realities, but is instead simply stating that apparently: Evolutionary Naturalism has a lesser probability of truth than Evolutionary Supernaturalism (in his view).

02:40 (2 minutes and 40 seconds)

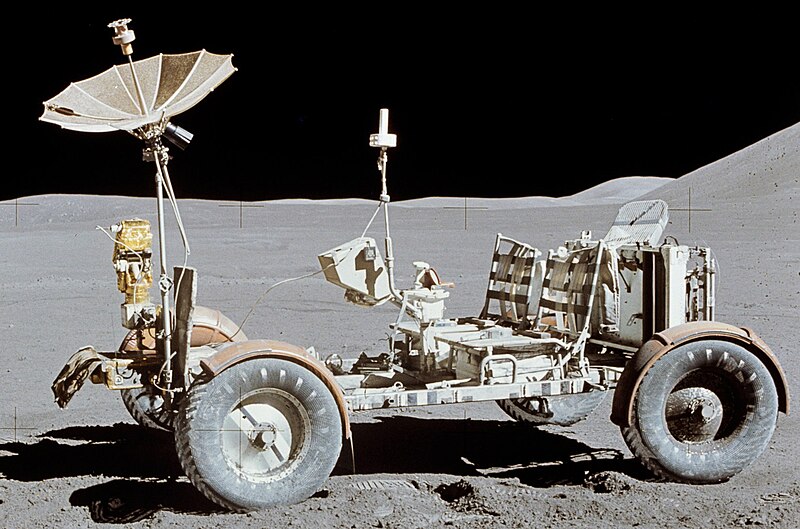

- “There would be agreement that there are indeed such things as automobiles… that [beings] use them to accomplish their purposes, which in the case of automobiles – normally – involves going somewhere… That automobiles won’t work well on the surface of the moon or the bottom of the ocean, that if you drop one out of a helicopter it will ordinarily fall down, rather than ascend… and so on…”

According to gravity, a car, not like objects such as sheets of paper, or parachutes, will fall through the air, like humans, at around 30-35 ft, per second per second. Once dropped, the car’s speed terminally accelerates to the point of terminal velocity wherein the medium (air) with which the car is traveling through, prevents further acceleration under gravity. Thus, all of Plantinga’s examples of these “truths” of the world and universe are pragmatic facts about reality, rather than philosophical musings.

Whether or not cars can drive on the moon or underwater is a semantical conundrum about how to define “car”. For example, do Lunar-rovers count as “cars”??

The same is true of cars driving underwater, since some of them can. It is also worthy of note, the kind of truth we are discussing here. It is truth about physical objects and entities such as cars, and alike. This kind of truth, as I briefly mentioned in the introduction can be labeled as empirical, and rational.

This is empirical knowledge because it is knowledge that comes to us through the senses, and as I have said in the past, I subscribe to the view that all is mere conjecture if it is not applicable via empiricism. There is still no one single “truth”, though, (in spite of the method by which we acquire “truths”).

I like how William S. Burroughs puts it in his essay “On Coincidence” in ‘The Adding Machine’: “Truth is used to vitalize a statement rather than devitalize it. Truth implies more than a simple statement of fact.”

Aside from the inductive nature of experience (which some Popperians ignore); we have a curious tendency of by-passing perspectivisms, which bundle their own truths in them. Surely, this deferring of perspective has a pragmatic function, but no more than the practical concrete representations of abstract or ideal mathematical shapes.

Every thing experiential is valuative and evaluative and generates differences, such that they may be comparable but not identical. In other words, the most that can be enjoyed is equivalence alone about pertinent facts. Even more, as a consequent, truths are paradigmatic and their constituent elements cannot be separated from the system in which it is contextualized, not unlike a field. Hence, a positivist’s referent is qualitatively not the same as an idealist’s, nor naturalists’ from supernaturalists’, nor a blind person’s from a schizophrenic’s, nor mine from yours, and so forth.

All that can be arrived at is the set of interacting truths, manifested as claims about perception communicatively, to produce yet another amalgam of truths, ad infinitum. This is not a classical dialectic being spoken of here, since there is not teleological point to it (only teleological paths within it.)

Empirical and Rational observation is our most finely tuned faculty, and is at the root of both science, and scientific naturalism. ![]()

03:05 (3 minutes and 5 seconds)

- “So our assumption is that when our faculties are functioning properly, though not always, such as when they’re are wokring at the very limit of their ability such as in contemporary physics and cosmology for example, that – for the most part – they will produce truth when they’re functioning properly … “

If it is really the case that our cognitive faculties as Plantinga says, were designed by the creator of the universe, ‘God’, to produce truth, then why do our cognitive faculties all have such a well established founding for error, at least so it would seem? I mentioned the McGurk effect earlier, but there is also the Monkey Business Illusion, visual trickery and many others. Plus: the Homo S Sapiens’ history of scientific error??

03:24 (3 minutes and 24 seconds)

- “But isn’t there a problem here for the naturalist? Or at any rate, for the naturalist who thinks that we’ve arrived on the scene after some billions of years of evolution, by way of natural selection, genetic drift, and other blind processes [ … ] working on sources of variation like random genetic mutation, [ … ] if that’s the way you think of it then shouldn’t it come as somewhat of a surprise that the cognitive faculties are in fact reliable?”

Isn’t there a problem here for the supernaturalist who falsely asserts that our cognitions are reliable and truthful? Plus, we have still yet to establish what Plantinga means here by “truth”. .. ???

If it is Plantinga’s contention that our cognitive faculties are god-given functions, and were designed by him, to, as I said earlier, produce truth, then why is it so evident, to repeat myself, that our ancestors made such a volume of mistakes, and so on? Our cognitive faculties are rarely if ever fully reliable. And also, Plantinga seems to argue that if both evolution(ism) and natural(ism) were both true, then the probability of reliable cognitive functions coming about are low. Apparently though, it IS low, since humans are only one species in the history of life. And also, the only example of a finely tuned cognition that he has given us so far, is our perceptual observations of cars.

06:15 (6 minutes and 15 seconds)

- “If Darwinism is correct, if Evolution is correct, or if the conjunction of evolution and naturalism were correct, then the ultimate purpose of our cognitive faculties would surely be survival … or perhaps survival by way of reproductive age, or to maximize reproductive fitness. So if they have a purpose then that’s what it is. Their purpose ISN’T to provide us with true beliefs, it’s to maximize fitness. …”

Yes. Our cognitive faculties only exist at all because of their predictive power. For example, eyes and the visual system is something that is said to have evolved independently among animals some 40 times throughout Earth’s history, as have many of the other senses, even though the eyes are probably the most pronounced one. And what is more, there are oceangoing invertebrates such as octopus and squid that have eyes on a par with the sharpness of our own. Or nautilus, with it’s sophisticated pinhole camera eye, as Dawkins phrased it so succinctly.

Evolution did NOT give us cognitive faculties to arrive at the most probable truths, nor is evolution a process with purpose or intent. It just plows on. “It” gave us cognitive faculties for survival purposes, as Plantinga has already said. And given the fact that not only can we only expect a certain number of our beliefs to be accurate and subject to revisions at any time, and there are far more ways to be incorrect in one’s beliefs than to be correct, how does Plantinga recognize the false points of his beliefs, if he believes that his cognitive faculties were designed by the all knowing creator of the universe to generate truth(s)? How could such cognitions ever be proven false, if Plantinga’s reasoning is sound?

Nevertheless, I am not alluding to post-modern theories of truths with my claims, but rather, I am simply stating that there are truths to be found using the vagaries of our perceptions, but it will not be the kind of truth that Plantinga would accept with his puerile clinging to certainty and security. All he is doing here is assuming the truth of his beliefs with no form of evidence, and his actual beliefs in question are meanwhile vague and immeasurable by any empirical means. While we can be very sure that cars and tables and chairs and such, exist, and that all of these objects have the properties that we commonly associate with them despite that we can only ever arrive at them through our limited perceptions. But; since are perceptions are highly unreliable, this is a very tentative form of ‘truth’, no matter how much you guys might protest! ![]()

We do not know that our current model of the world and universe and its formation, is really accurate in an absolutist or 100% certainty form. But the reason for that is because knowledge is axiomatic, and this is the way science now works, as a discipline and practice, through the principle of falsifiability, brought about by Karl Popper et al. Methodological Naturalism is simply pragmatic in it’s assumptions. It does not have to be certain in the same way that religious beliefs always have to. It only has to assume that it’s current picture, such as in scientific discovery, is more accurate, and more factual than any previous model.

I will skip the entire 3rd video, since he seems to spend the whole vid making baseless probability calculations, and quote-mining. So here’s the 4th video debunked.

Part 4 (skipped 3rd vid)

05:47 (5 minutes and 47 seconds)

- “By virtue of their content as well as their neurophysiological properties; and are also adaptive [to survive]. What then is the probability here of this possibility that their cognitive faculties are reliable? Well here I have to say, not as high as you might think. Beliefs don’t causally effect behaviours just by themselves, it’s beliefs and desires, and other factors that do so together. [ … ] So, Imagine that Paul is a prehistoric hominid, and the emergencies of survival cause him to display tiger-avoidance behaviour. [ … ] There would be many behaviours that [may be] appropriate, fleeing for example. Or climbing a steep face – assuming that tigers aren’t that great at rock-climbing … or crawling into a hole too small to admit the tiger [if] it is a large tiger. Or leaping into a handy lake. Now … when I wrote this I was under the impression that tigers, like house cats, don’t like water. [ … ] But in fact that turns out to be false. “

In this particular example, Alvin Plantinga admits that by not realizing on his part, that tigers can swim, and in fact, thrive in lakes and rivers, because of bizarre reasoning, assuming that tigers behave in a similar fashion to that of cats that are domesticated, and then changed his belief to the correct stance, after having learned more about it, Plantinga has now highlighted the flaws in this argument against naturalism. Naturalistic Evolution did not simply give us false or failing beliefs and desires. It gave us beliefs that most appropriately matched with the observed empirical data as you might call it, for our survival. And this IS important! And this is exactly why our cognitions may have been at least in some sense geared towards “truth” to a revisable degree, is exactly because of these survival advantages that come attached to discovering these “truths”, by virtue of our highly complex cerebral cortexes also “designed” by evolution. Plantinga’s beliefs about tigers not liking water may very well have got him brutally killed, if the situation occurred when he was faced with a tiger.

Plantinga’s tiger-illustration actually hits the nail quite well. He admits that his logically fallacious reasoning lead him to the erroneous conclusion as he later found out, that tigers are like other cats that he was familiar with. And at some time later, someone or other may have demonstrated to him that tiger in fact DO live in waters, such as rivers, and as such, Plantinga’s belief-forming mechanisms were shown to be false, and he had to change them in accordance with the empirically observed facts.

This illustrates the fact that beliefs are malleable and can change as new evidence comes along. And it’s that new evidence that matters, too. That is to elucidate the fact that beliefs are based on evidence, and few things are simply “self-evident”, as proposed by Evidentialist Foundationalism, in philosophy. Beliefs are not things that we merely accept because of the “fact” (LOL) that they were designed by god or gods to produce truths about the world, but we accept our beliefs based on empirically or rationally based justification for those beliefs, relating to the universe that we can observe. This also goes to demonstrate the rather glaringly obvious fact that the naturalistic world and universe is the first axiom of logic in regards to uncovering truths in reality, rather than God-given precepts, as Plantinga believes.

In his tiger illustration, Plantinga lists 3 possibilities of how a pre homo s. sapiens like hominid that he called “Paul”, could end up trying to run away from a tiger. His 1st possibility is that he would for some reason like to be eaten, but when faced with a tiger, giving in to his instincts, presumably runs away hoping for a better prospect, if he isn’t killed. The 2nd example, is that Paul may be led to believe that the tiger is in fact a large and friendly cat, which he wants to stroke … but apparently also believes that the “best” way in which to pet it is to run from it. The 3rd point is one we would all obviously concur with, from both our instincts and our educated standpoint as humans. That Paul believes that the tiger could damage or kill him, and he runs to prevent that from happening.

- 1.) So there is thus a conundrum in expaining how Paul’s false belief could naturally arise by evolution, if both evolution and theism are true. Given the fact that God could have designed the beliefs to ensure that they matched with reality. If Paul wants to be eaten by a Tiger, but then runs hoping for a better prospect, how is it possible for Paul to determine the prospects, in Plantinga’s mind?Whatever the causal reasons are for this avoidance-of-tigers behaviour, Plantinga cannot adequately explain how it could be inferred from observation, OR how it could be acquired as a new belief from experience or cognition, by virtue of our “unreliable”, according to Plantinga, Cognitive Faculties.

This, if true, can only be, under Plantinga’s Reformed Epistemology, a “properly basic” belief about reality, and thus his argument is ultimately self-refuting to Plantinga’s broader epistemological positions, if this argument is truly taken to its inevitable conclusions.

This, if true, can only be, under Plantinga’s Reformed Epistemology, a “properly basic” belief about reality, and thus his argument is ultimately self-refuting to Plantinga’s broader epistemological positions, if this argument is truly taken to its inevitable conclusions. - 2.) In the second example of Paul with his bizarre desire to cuddle and to pet the tiger, there is the same logical problem as before, but with added connotations. There are plenty of people who do in fact rather like the idea of cuddling up to a tiger, and some have in the past with relatively no injury. So what would stop a prehuman hominid like Paul from realizing this point?

- 3.) Finally is the false assumption that running away from a tiger is somehow a good or productive means of avoiding a tiger, when it is not., given the fact that tigers can run in excess of 35 mph, while the fastest humans humans can only run a 25 mph or so. And the fastest of tigers may average at 50 mph. As such, it would be more productive to use tools and weapons to fight the tiger, and shift your chances of survival a little.Thus, it seems that Plantinga can only use examples that never actually evolved, in order to prove his case. Plantinga in the 5th video then presents a hideous number of bizarre examples that are not really worth addressing. He spends his time endlessly repeating himself. BUT:Part 6 (skipped 5th vid)02:33 (2 minutes and 33 seconds)

- “The traditional theist on the other hand has no reason to doubt that his faculties are reliable, or that it is the purpose of our cognitive system to produce true beliefs. “

This is nothing short of a spectacular article of faith! Again, he is using the generic and unqualified term “theism”, and is not clear on what he means when uses the word “God”. It seems that he means the Judeo-Christian philosophy. But …. his term ‘theist’ applies to anyone who believes in God or gods. How does he know that a Demonic God could not exist and deliberately make our cognitive faculties Unreliable? Who is to make that judgement, and what is it’s significance if it is true? His whole argument would collapse, and so it seems that his entire argument is based on fundamentally flawed use of terms, and falls flat on it’s face on it’s first premise, that our faculties are reliable and truthful. Thus this argument is invalid, and is not a compelling argument against Evolutionary Naturalism. Thanks for reading.

Out-sources:

“Evolutionary argument against naturalism: An argument proposed by Alvin Plantinga (henceforth EAAN), which purports to show that metaphysical naturalism is self-defeating and hence cannot be rationally accepted. In addition, Plantinga argues that theism does not face self-defeat in the same way that naturalism does. In what follows, I shall descrive EAAN and outline some of the main objections to it.

To begin with, let ‘N’ stand for metaphysical naturalism, the claim that there is no God and nothing like God; let ‘E’ stand for the view that human cognitive faculties have evolved by way of the mechanisms that are studied by contemporary evolutionary theory; and let ‘R’ stand for the claim that the beliefs produced by those cognitive faculties are for the most part true.

EAAN has three stages, each of which involves defending a certain premise:

(1) P(R/N&E) is either low or inscrutable (meaning that we cannot determine whether it is low or high). Call this the Probability Thesis.

(2) Anyone who accepts N and E and the Probability Thesis has a defeater for R. This is the Defeater Thesis.

(3) Anyone who has a defeater for R has an undefeated defeater for each of his beliefs.

From these premises, it follows that anyone who accepts N and E and the Probability Thesis has an undefeated defeater for each of his beliefs, including his belief in metaphysical naturalism. But one who is a naturalist must accept E (it is, says Plantinga, the only option for the naturalist when it comes to explaining the diversity of life). Hence, naturalism is self-defeating. Let us see how these three premises are defended.

Plantinga defends the Probability Thesis by inviting us to consider the case of a hypothetical population of creatures on a planet a lot like earth, formed by blind, undirected evolution, and to assume that naturalism is true. What is P(R/N&E) specified, not to us, but to them? Plantinga notes that, when we consider this hypothetical population, there are four possibilities:

P1: There is no causal connection between belief and behavior.

P2: Beliefs are the effects of behavior but are not among the causes of behavior.

P3: Beliefs do causally affect behavior, but not by virtue of their content.

P4: Beliefs do causally affect behavior in virtue of their content.

Plantinga then says that, since these four possibilities are jointly exhaustive and mutually exclusive, the probability we want to assess, namely P(R/N&E), is given by the following weighted average:

P(R/N&E)

=

P(R/N&E&P1)P(P1/N&E)

+P(R/N&E&P2)P(P2/N&E)

+P(R/N&E&P3)P(P3/N&E)

+P(R/N&E&P4)P(P4/N&E).

The Probability Thesis is then justified by estimating this weighted average. P(R/N&E&Pi) is estimated as low for i = 1, 2, 3, because in these cases beliefs will be invisible to natural selection and so there will be no selection pressure towards their being mostly true. It seems, initially, as though P(R/N&E&P4) is going to be very high, but Plantinga contests this estimate by presenting examples of beliefs which are false but which, when combined with strange desires, lead to felicitous action. In the latter case, Plantinga concludes that the probability will be at best moderately high, not very much more than a half.

It now remains to estimate the probabilities of the form P(Pi/N&E), for i = 1, 2, 3, 4. Here, Plantinga thinks that, because of the enormous difficulties that naturalists (almost all of whom are at present materialists) face in avoiding P3, P(P3/N&E) is very high. Now, P1, P2, P3, and P4 are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive, and their respective probabilities sum to 1. Thus, each of P1, P2, and P4 must be estimated as having low probability on N&E. Plantinga claims that a reasonable estimate of the probabilities leads to an estimate of P(R/N&E) as being somewhat less than a half.

Plantinga grants, however, that estimating probabilities in this sort of context is a dubious business. So he concedes that it would be proper to take the relevant probabilities to be inscrutable to us, leading to the conclusion that P(R/N&E) is inscrutable to us. In this way, Plantinga arrives at his conclusion that P(R/N&E) is either low or inscrutable.

In his self-profile in this volume, Plantinga has given a new argument for the Probability Thesis, which does not consider different possibilities for the relation between belief and action, and which supports the stronger conclusion that P(R/N&E) is low (rather than the conclusion that it is low or inscrutable).

The Defeater Thesis is defended by appealing to hypothetical cases that, it is claimed, are clearly analogous to the case of the naturalist in EAAN. Since, in these cases, the subject has a defeater for R, the same is true of the naturalist who accepts the Probability Thesis. Two hypothetical cases that have tended to predominate in discussions of EAAN are The Case of the Cartesian Demon and The Case of the Drug XX. The former is described below, and a version of the latter is described in Plantinga’s self-profile in this volume.

The Case of the Cartesian Demon

Suppose a man comes to believe that he is the creation of a demon that, as imagined by Descartes, is immensely knowledgeable. Suppose that he also comes to believe that this demon is not particularly concerned with making his creations cognitively reliable, and on at least some occasions has been quite pleased to make them unreliable, and moreover has made them unreliable in such a way that they continue to think of themselves as paragons of reliability, being unable to detect the cognitive disaster that has befallen them. Thinking about this, the man comes to the conclusion that P(R/D) is low or inscrutable, where R is specified to himself, and D is the proposition that the man has been created by the demon. Then the man has a defeater for R.

Plantinga defends the third premise by arguing that, if the naturalist has a defeater for R, this generates a defeater for the rest of his beliefs as well. The reason is that all of the naturalist’s beliefs are products of his cognitive faculties, which constitute their source. Once the reliability of that source comes into question, so do the beliefs generated by the source. Moreover, the defeater for R that the naturalist acquires cannot itself be defeated, since everything that could be a defeater-defeater is itself subject to defeat. To support this, Plantinga says that to rely on one’s cognitive faculties to form a defeater-defeater of the defeater one has for R would be like trusting a man to tell you he is not a liar when you have already been given excellent reasons to doubt his honesty.

Let us now consider some objections to EAAN. Most of the controversy regarding the argument has focused on the Defeater Thesis. There has been one main worry that critics have had about this claim. The objections to it that we shall describe are manifestations of this worry, which can be expressed as follows: what exactly is the connection between the naturalist’s acceptance of the Probability Thesis on the one hand, and her acquisition of a defeater for R on the other? One of the most natural expressions of this worry is the Perspiration Objection

The Perspiration Objection

The probability that the function of perspiration is to cool the body given (just) N&E is also low. But surely it would be absurd to claim that this gives the naturalist a defeater for this belief. Thus, it is also absurd to claim that the naturalist has a defeater for R in virtue of accepting the Probability Thesis.

There is no defeater in the perspiration case because the naturalist has other evidence for his beliefs about the function of perspiration, beyond just N&E. So could not the naturalist appeal to other evidence for his beliefs about R? This thought leads naturally to the Total Evidence Objection for EAAN.

The Total Evidence Objection

The naturalist has many other beliefs besides N&E. The probability of R relative to N&E conjoined with these other beliefs is quite high. Thus, the naturalist need not have a defeater for R in virtue of accepting the Probability Thesis.

Many philosophers (including Plantinga) hold that, in addition to propositional evidence, beliefs can also be warranted in virtue of non-propositional evidence. This leads to yet another objection, due to Michael Bergmann, which we can call the Non-propositional Evidence Objection.

The Non-propositional Evidence Objection

Even if R has low probability on all the available propositional evidence, the naturalist could still have non-propositional evidence for R which makes it rational to continue to hold on to R. Hence, the naturalist need not have a defeater for R merely in virtue of accepting the Probability Thesis.

These objections comprise just a small sample of the arguments against EAAN that have appeared in the published literature on the argument. Many of these, along with Plantinga’s responses to them, are articulated and discussed in Beilby (2002 [Naturalism Defeated? Essays on Plantinga’s Evolutionary Argument]).”

(“Evolutionary argument against naturalism,” by Omar Mirza. In A Companion to Epistemology, 2nd ed., edited by Jonathan Dancy, Ernest Sosa, and Matthias Steup, 351-354. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.)

As for the technical term “defeater’ –

“Following Pollock (1986), we can distinguish between undercutting and rebutting defeaters. Intuitively, where E is evidence for H, an undercutting defeater is evidence which undermines the evidential connection between E and H. Thus, evidence which suggests that you are a pathological liar constitutes an undercutting defeater for your testimony: although your testimony would ordinarily afford excellent reason for me to believe that your name is Fritz, evidence that you are a pathological liar tends to sever the evidential connection between your testimony and that to which you testify. In contrast, a rebutting defeater is evidence which prevents E from justifying belief in H by supporting not-H in a more direct way. Thus, credible testimony from another source that your name is not Fritz but rather Leopold constitutes a rebutting defeater for your original testimony. It is something of an open question how deeply the distinction between ‘undermining’ and ‘rebutting’ defeaters cuts.

Significantly, defeating evidence can itself be defeated by yet further evidence: at a still later point in time, I might acquire evidence E’³ which suggests that you are not a pathological liar after all, the evidence to that effect having been an artifice of your sworn enemy. In these circumstances, my initial justification for believing that your name is Fritz afforded by the original evidence E is restored. In principle, there is no limit to the complexity of the relations of defeat that might obtain between the members of a given body of evidence. Such complexity is one source of our fallibility in responding to evidence in the appropriate way. ”

(http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/evidence)

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/reasoning-defeasible

Of course, Plantinga did not need to reveal his bizarre ignorance of philosophy, metaphysics, biology, and Palaeoanthropology, by using his equally bizarre tiger examples. There are excellent examples of definitively false beliefs that have lead to better outcomes than ones that are “true”, to whatever standard. Take the placebo effect. Its not just a change of perception, it has measurable effects. Of course, Plantinga is not going to use real-world examples in his lecture, because his own beliefs are not based on anything real, and needs his Christian beliefs to appear at least somewhat more likely to be true at the end of his lecture. As I said, what kind of evil and disingenuous being would create us to have false beliefs? Then again, how could we disprove such a notion…? But if we don’t look at the examples of genuinely beneficial false beliefs that actually exist, and judge their value, we will fail to understand how false beliefs themselves can evolve. Plantinga sets himself up to fail in understanding false beliefs, and does so via a very selective attempt at looking at all the available evidence. Beliefs are part of an evolutionarily unique way of avoiding becoming trapped with mere instinctual mechanisms. Thus we need to examine not only whether or not the conclusions themselves are sound, but whether the method by which we arrive at them is also sound, be they mathematics, logic, deduction, induction, empiricism, abstraction, metaphysics, etc. What we’ve done with our scientific models is to produce a predictive instrument designed to weed out false theories and apprehensions, and it is through this method that it can be seen that Plantinga’s arguments can be seen to be invalid. That is why he want’s to destroy naturalism, even at the methodical level …

15 thoughts on “Critique Of Alvin Plantinga’s Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism”