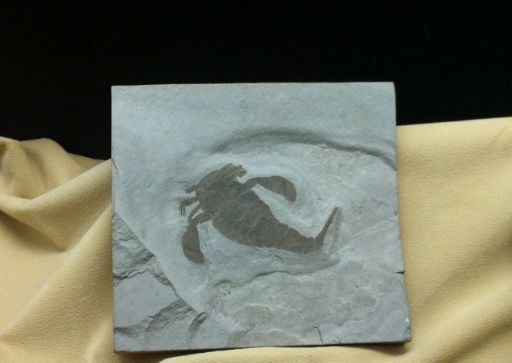

Last month’s challenge appeared to be no challenge to League of Reason’s resident rockhound Isotelus. She gave the correct answer within a day of the blog going up.

Edmontosaurus annectens. They’re like the cockroaches of Alberta’s fossil megafauna. Dig a hole and you’re probably going to find at least a piece of one.

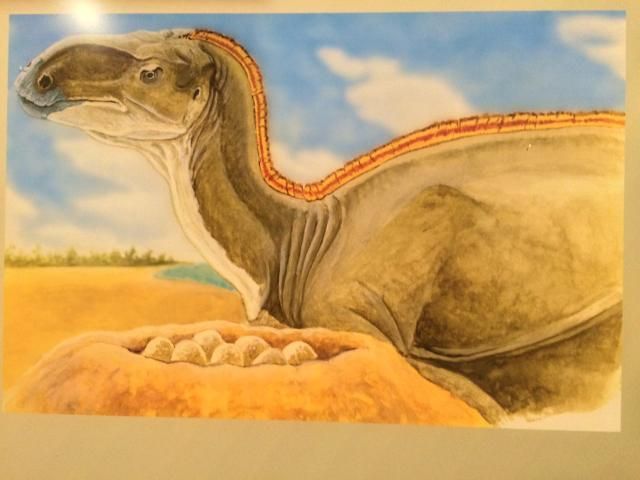

This critter is indeed Edmontosaurus annectens and it is indeed an extremely common fossil.

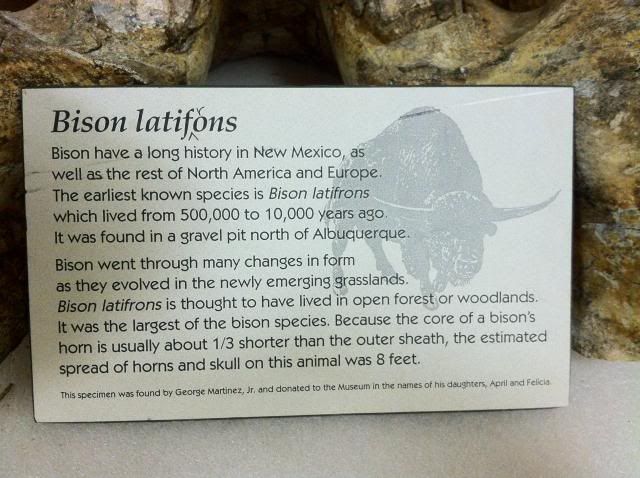

(Taken at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science)

Edmontosaurus lived during the Cretaceous 73 to 65.5 million years ago. They ranged widely across western North America, seemingly living along the Western Interior Seaway. Edmontosaurus belong to the hadrosaurid clade, which are popularly called duck-billed dinosaurs. Edmontosaurus belongs to a crestless group of hadrosaurid, unlike a previous “Know Your Bones” challenge. The specimen used in last months blog is actually famous for having what appears to be a bite mark on its tail from a Tyrannosaurus.

Edmontosaurus reached a length of ~13 meters (the skull alone was ~1 meter long) and could weigh up to 4 tons, making them one of the largest hadrosaurids to have ever lived. As a means of locomotion, Edmontosaurus were likely able to walk on all fours or on just their hind limbs. Edmontosaurus is also famous for having several skin impressions, which allows us to know what most of the skin of this animal looked like in life. Edmontosaurus had teeth that grew in columns of six teeth, and had around 50 columns in each jaw. The teeth were continually replaced throughout the animal’s life. However, the beak of an Edmontosaurus was toothless and was extended by a keratinous material, much like modern birds.

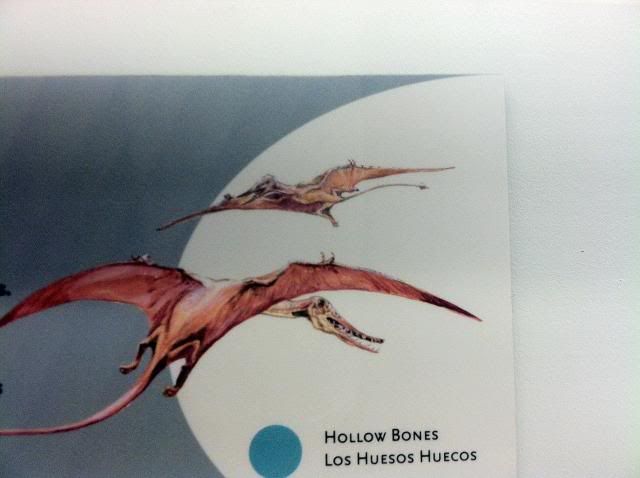

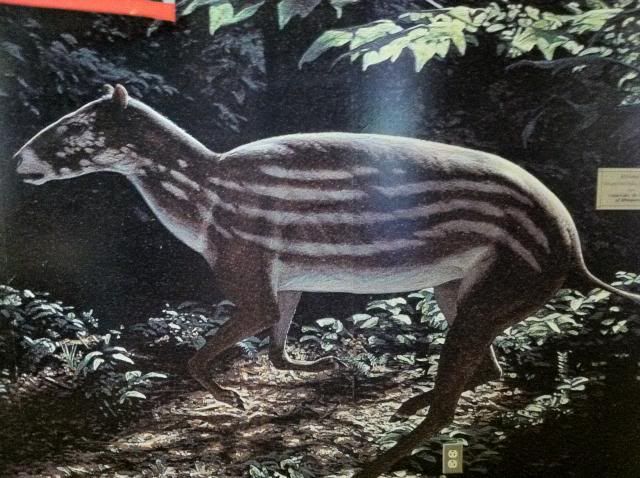

Moving on to next month’s challenge:

(Taken at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science)

Good luck, as always.