Last month’s challenge led to some great guesses early on. However, the win goes to two of the later commenters. Last month, I was not looking for a specific species, but the name of the group, which makes our first winner Dragan Glas.

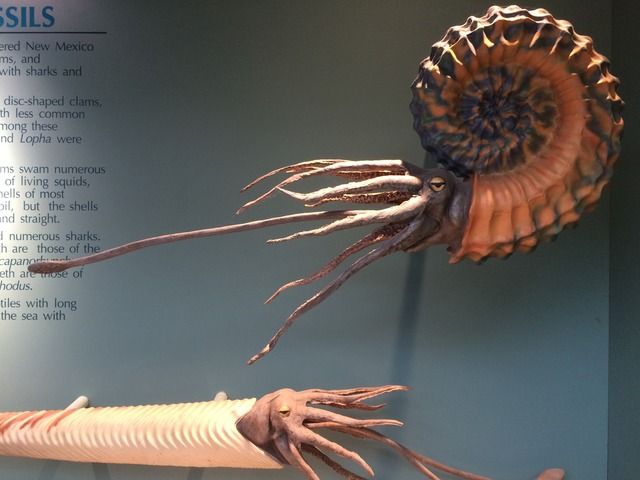

Ammonites

The critters are indeed ammonites (Ammonoidea). However, a minute before Dragan Glas’s guess, red also made a correct guess:

Perhaps otherwise – Coilopocerus nova mexicanus

The specimen labeled number 3 is a Coilopoceras springeri. The species is incorrect, but being able to nail down a specimen to a genus level from just a single photo is amazing. Specimen number 1 is Romanicera mexicanum and specimen number 2 is Spathites puercoensis.

(Taken at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science)

Ammonites lived from the middle Devonian until the end of the Cretaceous giving them a temporal range of 400 to 66 million years ago. Ammonites are a common fossil in Paleozoic and Mesozoic marine deposits across the world. These critters would have made up a huge amount of the biodiversity of any sea during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic. Most species of ammonites have the spiral shape seen by the three species from last month’s challenge, a few others had spirals that resemble the modern nautilus, others had straight cone shaped shells, and still others had fancy shaped shells (heteromorphs). However, some of the spiral shape shelled ammonites could grow some fancy spikes to ornate their shells as well.

Ammonites make great index fossils, because they speciated quickly and distinctly. Thus, identifying a species (or group of species) of ammonite can actually pin down the date of a location. Ammonites can range in size from as small as 23 cm to ~2 meters in diameter. Although ammonite shells are very common, the soft bits of their body are not and very little is known about it. However, ammonites are believed to be carnivorous (like most swimming cephalopods), had a beak, and perhaps ten arms. Ammonites survived a few mass extinction events, including the end Permian extinction (the Great Dying), but finally went extinct during the K-Pg event that also took the non-avian dinosaurs.

Moving on to next month’s challenge:

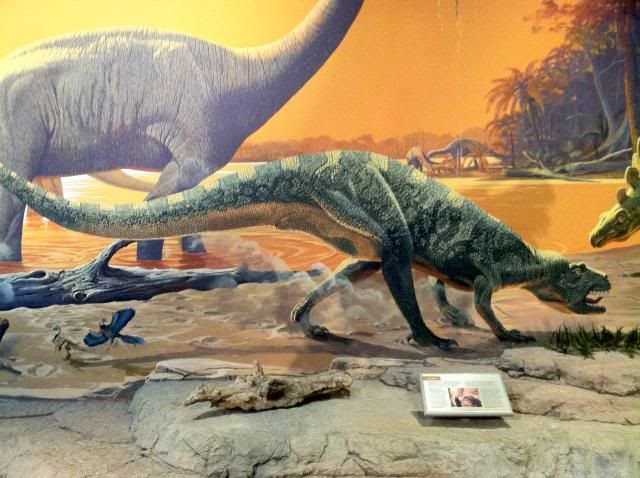

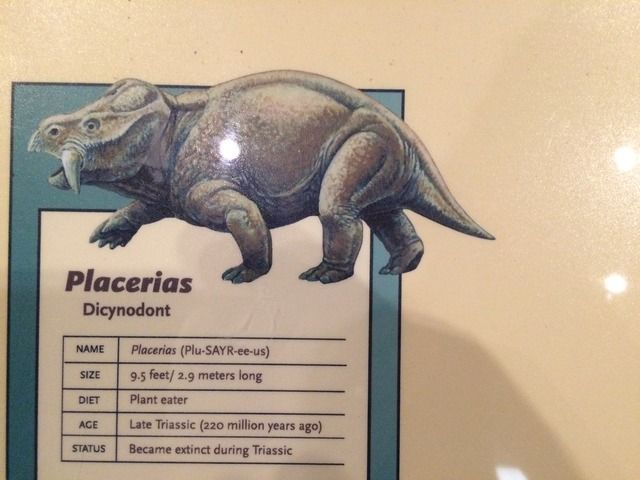

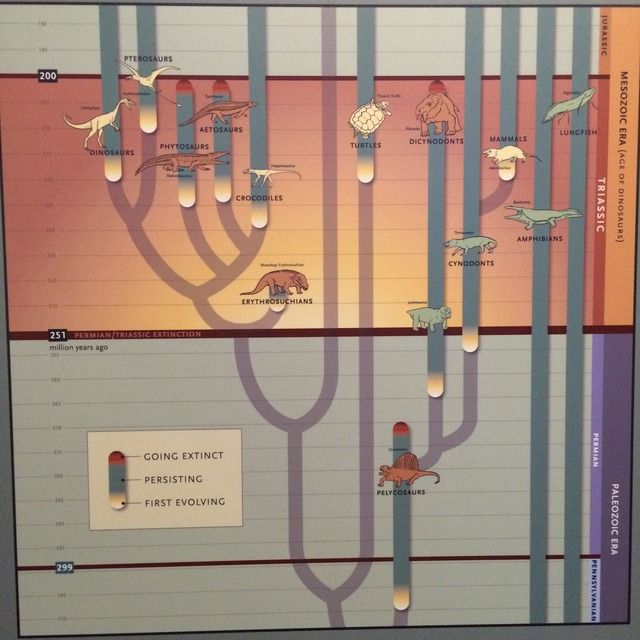

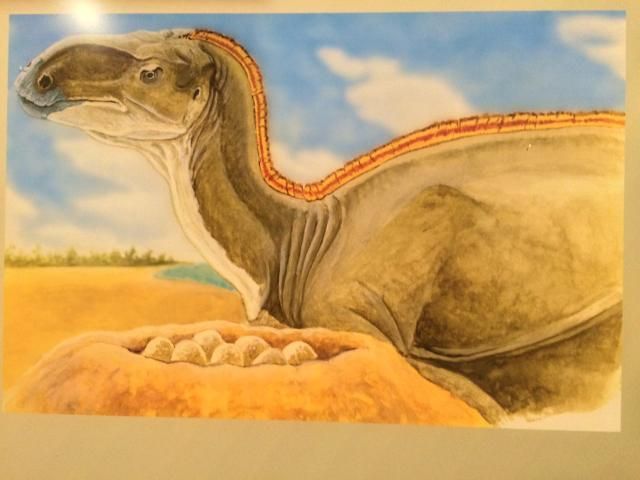

(Taken at the Dinosaur Museum and Natural Science Laboratory)

Thanks to everyone that is playing and I am hoping to read some more great guesses this month.