Last month’s challenge is a true titan. It held the record for being the largest dinosaur for several decades. So, who was able to name this giant? Isotelus once again named this critter.

Brachiosaurus. I would guess the species name starts with an ‘a’

This is indeed Brachiosaurus altithorax.

(Taken at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science)

Brachiosaurus roamed 145 to 150 million years ago, during the Jurassic (and possibly the early Cretaceous) across the Western U.S. Brachiosaurus shared its range with several other sauropods and an earlier Know Your Bones critter. Brachiosaurus was ~25 meters in length, ~13 meters tall, and it had an estimated weight of ~28 tons, making it a true giant by any standard. Unlike most other dinosaurs, Brachiosaurus had longer forelegs than their hind legs. This curious trait is where it gets its genus name from (Brachiosaurus literally means, “arm lizard”).

Brachiosaurus was an herbivore, most likely feeding off the tops of fern trees that the other sauropods could not reach. Its large body would have been more than enough protection from predators that lived at the same time. It probably took a Brachiosaurus ten years to reach full size and could eat up to (if not more) ~182 kg of plant matter a day as an adult.

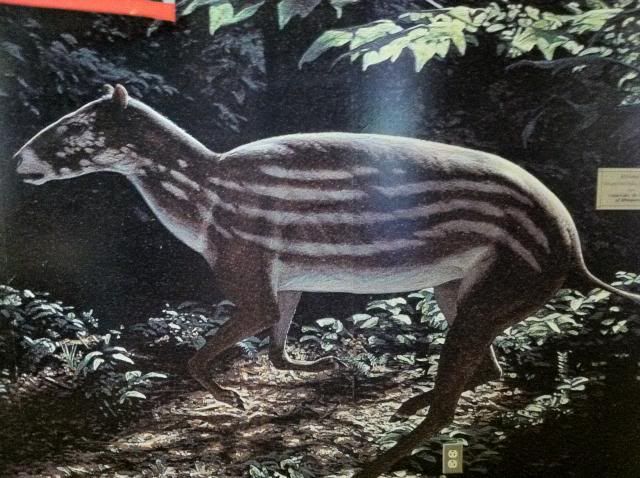

Moving on to this month’s challenge:

(Taken at the Dinosaur Museum and National Science Lab)

Good luck to all.